September 24, 2019

F1 and Tourism

Just saw this article about the upcoming F1 race in Hanoi (upcoming in the sense that it is April 2020). It will be hosted by VinGroup, which is both surprising and not. This will be the first time that Hanoi hosts the F1. Notably, a bunch of the F1 sites in developing markets have fallen by the way-side over the years. Specifically:

Source: formula1.com

The Malaysian Grand Prix was an F1 race 1999 to 2017 (and an prior race went back to 1962 in Singapore). The government decided to stop hosting it because: “The race costs £50 million just to win the rights and the government were unable to justify the ongoing spend. ‘I think we should stop hosting the F1. At least for a while,’ said Malaysia’s youth and sports minister Khairy Jamaluddin. ‘Cost too high, returns limited. When we first hosted the F1 it was a big deal. First in Asia outside Japan. Now so many venues. No first mover advantage. Not a novelty.’”

The Korean Grand Prix was held from 2010 until 2013. It looks like there was a dispute between the Korean organizers and F1 management. In 2012, the Koreans were already saying it was too expensive. “This year [2012], the local organizer expects a loss of more than $26 million.”

The Indian Grand Prix was another short one - 2011-2013. This time it was tax issues with the government - they wanted to characterize the race as entertainment and levy an entertainment tax. Also, “the organisers have already been struggling with rising costs and poor revenues.”

I am sure there have been more countries that hosted races and no longer do, but basically it looks like figuring out how to make a profit is a big issue. The F1 parent machine gets lots of money from all of the fees they charge. The organizers also have to pay to put on the race and to market the race. That doesn’t count the cost to build a track or fix up the street for a race. For example, Abu Dhabi built the Yas Racetrack for $1.3bn. Even a street race can cost $1bn for 10 years of hosting. Vietnam’s race is expected to cost $200 million, all funded by private companies.

Source: Formula money

There is a lot of revenue to justify these expenses: TV rights and ticket sales. These are a lot, but not always enough to cover the costs. And in a country where it is hard to charge very high ticket prices (like India and Malaysia) and TV rates are lower, it just can’t be justified.

And sponsorship revenue is falling, not helped by restrictions against tobacco companies sponsoring teams. That means that teams have moved on to tech (whose interest is…disappointing), fashion and beverages (Red Bull and Martini being the big ones).

But of course, the worldwide audience for these races is high: 490 million people in 2018, according to the F1 organization. Although that seems like a crazy and untrue number. Supposedly it fell 18% in the past 11 years, which, if I am doing my calculations right, would mean that almost 600 million people watched a F1 race on TV back in 2007. That’s more than 9% of the world’s population. For a race that is only held in 21 countries and hasn’t been consistently held in India or any of the Americas. Seems crazy to me, and very unlikely. But I guess they have internal numbers.

Why is Vietnam doing this? Vietnam is expecting a boost to tourism revenues from all the people visiting, and it wants to show the world that it is a real country that plays with the big boys like Japan, Europe, the US, etc. And Vietnam has been trying to host more of these worldwide events, just like the Trump-Kim summit earlier this year.

Unless they got a great deal with F1, VinGroup will surely money on this, but they can write it off as marketing. And the government will be happy with them.

I have my fingers crossed.

September 23, 2019

Vietnam beats renewables goal a year early

Sorry about the missed post on Friday, I have been busy working on the website. Hopefully things will be finished shortly.

Big news out from Vietnam - the country has already beat its target for energy from renewables. The government had set a target of 7% from renewables by 2020, and it is already at 9%, according to this story.

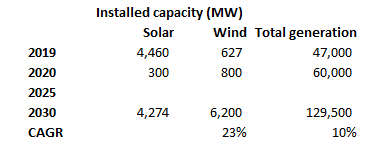

Source: Moit by way of IEFFA

As of July the country's solar energy capacity was 4,543 megawatts (MW) and wind power capacity was 626.8 MW, Le Hai Dang, a strategy board member at Vietnam Electricity (EVN), said at the opening of the 2019 Vietnam Renewable Energy Week held in Hanoi on Tuesday.

Looking at a few different sources, it looks like right now the government would like to have 21% of energy coming from renewables by 2030. Those renewables include biomass, small-scale hydro, solar and wind. Of that 11% of the total energy mix should be wind and solar.

Part of the big success is due to this new solar farm in the south, about 100 km from HCMC, and which will power 320,000 households. There are 10 projects in this one province, Tay Ninh, with 9 of them already in production. Another province, Dong Nai, also in the south, is proposing 8 projects with 5,400 MW capacity on the Tri An lake. The big rush to approve these projects by the end of June was due to the expiry of its feed-in-tariff (FiT) agreement:

Vietnam saw rapid construction of new renewable power plants in the first half of this year as investors sought to beat a June 30 deadline to enjoy price incentives of 9.35 U.S. cents per kWh feed-in tariff for the next 20 years.

This is despite somewhat weak PPA terms that have kept some investors away (as I have heard personally and as the IEFFA reports). The big concern, and we have talked about this before, is that the utility EVN can terminate the agreement or curtail buying electricity if the grid doesn’t hold up. Also, “international investors have lacked confidence in the credit standing of…EVN.” But even with these, the companies have been able to get these plants built. I would assume it is because the pricing is good and they have reassurances that the grid will be able to take any electricity produced. EVN is starting to work on upgrading its grid, so that probably helps.

As I said, the FiT ended June 30, and there is not yet a new feed-in-tariff (FiT) agreement from the government, so we will see a slow down in new capacity builds in the near future. There is a draft FiT right now, but it hasn’t been approved.

Long term, fossil fuels (coal and natural gas) are tough competitors for renewables in Vietnam. First, the country has a fair amount of coal plants, and they are somewhat cheap. Because of that and their need for lots of energy, Vietnam doubled coal imports in the first four months of the year. Tied to that, expectations are for natural gas prices in the US to continue to be extremely low (less than $2 per mmbtu). This has already lead to the gas-powered electricity plant we talked about in the last post.

I really hope that the government continues to prioritize renewables through their new solar FiT, for the sake of health, climate change, but also the current account balance. Ultimately, renewables are going to be cheaper than the alternatives. But it might take some time before everyone realizes that.

September 19, 20190

Even more on gas

Tech note: the blog is loading very slowly because of the way that I set it up (as one long page). I am working to fix that. One day you will open to a page that loads more quickly and is a completely different format. Until then, sorry about the snail’s pace of the page.

Natural gas prices. Source: markets insider

I grew up in Louisiana, USA, and I have a very soft spot for the state (motto: Thank God for Arkansas!). It has it’s problems, and my views is that it is partly due to the oil and gas industry, which has just such perverse effects. There are a lot of rich people in good times, and that trickles down some, but then there is a bust, and everyone gets poor. Right now we are coming off the fracking riches.

But because fracking has drastically changed the natural gas market in the US and driven down natural gas prices (see price chart on right), two companies have built LNG terminals in the state. One in Baton Rouge just signed a long-term contract with a new power plant in South Vietnam.

The contract with Delta Offshore Energy and the government of Bac Lieu province will be for 2 million metric tons of LNG annually for 20 years.

You can read a press release here about the project, which is expected to begin operations in 2023. Total capital invested is $4.3 billion according to this article.

So big investment in power plants in the south. Pretty interesting. Also shows how the US gas market is searching out new markets and is successful in finding them.

Natural gas is better for the planet than coal but not as good as renewables. But given that Vietnam is drastically increasing its greenhouse gas emissions at the same time it is suffering from climate change, this may be the only way to limit that increase.

September 18, 2019

More on oil and gas in the South China Sea

A while ago I read Daniel Yergin’s book, The Prize, which is all about oil and the oil business (to be honest, I didn’t read the whole thing: it’s long!). Two things stuck with me: 1) Germany and Japan basically lost World War II because they didn’t have enough oil/fuel. And 2) Russia lost the Cold War because oil prices fell and wrecked its economy.

I starting thinking about that today because I am seeing stories about China, South China Sea and its efforts to stop Vietnamese oil and gas production. Or I guess, China needs oil, and the South China Sea is the closest oil field readily available.

The biggest near-term threat to Vietnam’s efforts in the sea is to its Ca Vau Xanh project, or Blue Whale, a project that Exxon is working on with PetroVietnam. There is speculation that China is putting pressure on ExxonMobil and/or Hanoi to stop the project. The speculation comes from social media, news outlets and and experts writing in these outlets. An alternative theory is that Vietnam is haggling over gas prices, and that is stalling the project. These negotiations may be happening but they are very unlikely to stop the project - Vietnam needs it too much. .

We talked yesterday about Vietnam being a small new fuel importer, but that small is going to turn into big if projects like Blue Whale don’t go through. Plus, while it is somewhat easy (albeit expensive) to import fuel, you have to build power plants that can convert that fuel into electricity to power your booming manufacturing base. That is already a problem in Veitnam’s south, and is expected to result in country-wide shortages in 2021. According to the this article:

Vietnam Electricity, PetroVietnam and Singapore’s Sembcorp are currently holding talks to build and operate two power plants to convert the gas [from Blue Whale] to 2 Gigawatt of electric power. This would amount to ten percent of Vietnam's current total power demand.

Vietnam needs this project. And China really doesn’t seem to want Vietnam to have it. Needing to have physical access to the oil wells seems a bit weird to me these days. Oil and gas are globally traded. And, while occasionally expensive, have generally been available. I guess in the case of war that’s not true (remember Yergin), but it seems like war is a ways off.

So what would happen if Exxon pulled out:

Gas prices would like rise, because Vietnam would have to import more fuel.

Manufacturing businesses would suffer, because they would face higher costs for electricity, and, if shortages come through, potential lack of stable electricity supplies.

There would also be pressure on the current account side, because the country would have to import more fuel.

And pressure on the fiscal budget. According to the last article, the Vietnamese government is expected to make $20 billion from this project. That’s a lot of ducats that need to be replaced.

Vietnam’s use of coal would jump, because there is no domestic replacement for this gas. But there is domestic coal, a fair amount of it, in fact.

There would be more investment in renewables. This would be very positive in the long term, but will be costly for Vietnam in the short term. And doesn’t replace the lost revenue.

There would likely be more riots against Chinese companies, because regular Vietnamese would think (rightly or wrongly) that China pressured the company to pull out.

Vietnam is not able to pull out of this deal, so I expect that from the government’s side, it will do whatever it can to make sure it still happens. The US government also wants it to happen. ExxonMobil’s calculation is more difficult, because China is such a large importer of fuel. It will be interesting to watch.

September 17, 2019

Oil prices

Oil prices in USD. Source: Markets insider

I probably should have written about this yesterday, but I didn’t. Anyway, oil prices are way up (15% yesterday, although down 1.5% today) after the attack on Saudi Arabia’s oil infrastructure. And if the US decides that it needs to attack Iran, then we could see more spikes.

But looking closer, I am not sure that we need to be so worried. First, oil prices are not that high. Brent was above $70 per barrel at one point yesterday, but well below where they were in August 2018 (close to $90).The world didn’t explode then.

We are seeing slowing GDP growth plus increased investment in renewables and public transport globally, so I am not sure that we are going to see tons of pressure on oil prices long term. That means this might be a big spike for a few months but likely well below the highs we saw back in the early teens. Remember from February 2011 to September 2014, oil prices were consistently above $100 per barrel. Of course, predicting oil prices is a mug’s game, but, what the hell, I don’t think we are going to see that $100 price again.

Source: Vietecon.com

Second. Vietnam just doesn’t import that much oil. According to the CIA (!), it imported just 23,700 barrels a day, or 8.7m a year, which would cost the country $606m. If the oil price went up to $80 per barrel, then that would be $692m. Vietnam is a net importer of fuel, and the trend is negative (one reason why I believe the country should invest in renewables), but it is still relatively small. Net fuel imports were about $4bn in 2017, which pails in comparison to the almost $14bn in net electronics imports (most of which likely went into goods that they they exported). The country has a big current account surplus, so they are fine if oil (which is well below 10% of merchandise imports) rises a little.

So ultimately, Vietnam should be able to weather this much better than other countries. For example, Japan imports 3.2m barrels a day, so a $10 increase in oil prices raises its yearly import bill by $11.6bn. In ASEAN, Indonesia is the largest importer at 907,900 bbd, so that same $10 increase costs it $3.3bn a year. That’s low compared to its GDP, but still a lot of money. Thailand would face a similar bill, but on a GDP that is about half of Indonesia, so it’s even worse for them.

Basically, Vietnam is in better shape than its ASEAN neighbors in regard to energy.

September 16, 2019

Work patterns and joining the labor cycle at different points

Let’s start with telephones: In many developing countries, it used to take forever to get a telephone line. In India, a customer requested a telephone line in 1965, and by 1983, still had 5 more years to wait! Egypt, where I lived, was similar. It was key to rent a place that actually had a telephone, because there was no way you would get one. After many years, mobile phones arrived, and boom, everyone had one. In 2015, there were just 26 million landlines, compared to 970 mobile phones in India. Basically, India had a sclerotic telephone company that couldn’t service the country (for both economic and regulatory/monopoly reasons), and then mobile phone companies were able to leapfrog the fixed line company very quickly for much less - just a transmission station rather than lines to every home.

Electricity is the new frontier: We are seeing a similar thing with solar electricity generation. It can be very expensive to bring in power lines to remote villages in Africa or India, but a solar panel allows for cell phones to be charged, lights to work at night and water pumps to be electrified.

Vietnam has been a beneficiary of these trends as well. There were only 14m landlines in Vietnam in 2017, but 128m mobile phones (more than the number of people, because some people have more than one). There is even off-grid renewable electricity in Vietnam.

This is a bit of a jump, but another area where we might be seeing some of this leapfrogging is in retail. The formal retail market in Veitnam is growing (as I talked about last week with VinGroup/VinCommerce), where consumers are moving from traditional markets to formal stores like grocery stories, etc. But in the West, we are hearing a lot about the “retail apocalypse,” with a number of stores closing as e-commerce grows.

Now there is a study out by the Institute of International Finance that looks at this through the lens of employment and productivity:

Job losses in US retail have been a persistent feature of the US labor market for many years…The underlying issue is a wide efficiency gap between “brick-and-mortar” retail and e-commerce. We calculate the number of employees needed to generate $1 million in sales per year in different parts of the retail sector. Department stores need 8 employees, while electronic shopping & mail-order houses, the category that captures e-commerce in the establishment survey, need as few as 0.6.

e-Commerce sales. Source: google & Temasek

Now this doesn’t count all of the people that are involved in delivery the products to the final customer. Right now, getting to the store and picking up product is all from the customer. Going forward, this will be partially taken over by delivery people, who are likely to be paid less (but maybe not too much less) than retail salespeople. So fewer people, paid a bit less.

As e-commerce sales grow, there will be fewer jobs in brick and mortar retail that are unlikely to be replaced by delivery people 1:1. And retail employs a lot of people. In Vietnam, the service sector makes up 34.4% of all employment, and wholesale and retail trade makes up about 20% of all employment, the third largest sector (after agriculture and manufacturing). According to the World Bank (and we have talked about this before), farm workers made up 65% of the labor force in 2000 but that declined to 46% in 2015. That’s a gigantic decline, and those people have to go somewhere! And this is only the start.

Right now, most go into manufacturing, but that will depend on Vietnam continuing to be attractive to manufacturers, and the trade war puts some of that at risk. Other could go into retail stores, which requires not much education (good for rural workers who don’t have as much access to secondary or tertiary education).

Online transport & food delivery. Source: Google & TEMASek

But Vietnam may find that these retail jobs just aren’t there, because they have been made redundant by e-commerce. This is no idle threat: e-commerce gross merchandise value has grown from $400m in 2015 to $2.8bn in 2018. And it is expected to grow to $15bn in 2025.

This should be helped by a growing delivery market. We can see this in online transport and food delivery, which was $200m in 2015, grew to $500m in 2018 and is forecast to grow to $2bn in 2025. So some jobs will go into delivery, but the live of a delivery person, even if paid as well, is just not as good as a store salesperson.

To counteract this, Vietnam really needs to educate people so that they can find better service jobs and also hopefully higher-end manufacturing. Having local innovation would be a key part of this. But that’s quite up the curve from where the country is now. Korea did it, although had a better head start and an industrial policy that was very smart. I am not sure that I am seeing that in Vietnam. At least not right now.

September 13, 2019

Big news: Central Bank lowers interest rates!

So the big news today is that the Vietnamese central bank cut policy rates by a quarter of a point to 6.0%. This is the first cut since 2017. And back then it had been almost 2 years before that the rate had been cut (by 50bps). So this is a big deal. And it appears mainly driven by concerns over global economic conditions, not because of weakness in Vietnam’s economy. So what happened and why:

percentage change in Consumer prices in ASEAN. source; world Bank

The stock markets rose. Ha Noi (HNX30) is up 1.2%, while HCMC’s market (VNINDEX) rose a similar 1.14%. Stocks love lower rates, especially if the move isn’t especially a signal of recession (and even if it is).

When rates fall, stock prices rise for a few reasons. Companies benefit a bit from lower interest payments, although it’s fairly marginal. Also, bonds will look less attractive than stocks on a relative basis (the return is less). Plus, the present value of future cash flows is a bit higher (it is discounted at a lower rate, which is positive for present value).

The reason the central bank could do this is because inflation really is not a concern. Not in Vietnam, not in ASEAN (see chart to right), and not globally (CPI rose just +1.7% yoy in the US). Consumer prices rose 3.5% in 2018. This year doesn’t seem to be a concern - the forecast is below 3%.

This is another example of a central bank focusing more on global trends than on local ones. We talked this in the context of the Fed yesterday, but it turns out that it’s true for every central bank.

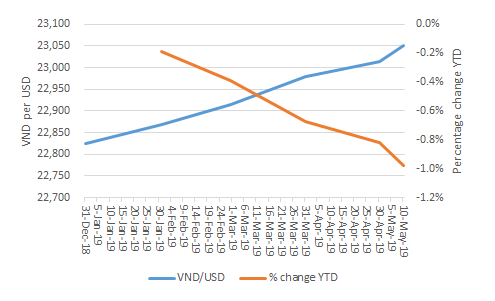

This might make it a bit harder to maintain the exchange rate, although there didn’t seem to be much stress on the currency market today. Why? Well, you might see investors less interested in buying Vietnamese bonds. If they aren’t buying bonds, then they aren’t buying the currency, and the currency might fall. But the VND isn’t floating, so that’s not happening.

This leads me back to my perennial concern: debt not denominated in VND is dangerous and doesn’t allow as much leeway with local interest rates. But no one is going to listen to me. Probably for good reason.

Congrats to all the people that made money on this surprise announcement!

September 12, 2019

Equity versus Debt

I saw this article in Bloomberg about capital raising in Vietnam. Quick summary: equity raising (at least through the public markets, like IPOs or secondary transactions) have been very small, but debt has grown quickly. According to their numbers, debt issuance has been $5 billion compared to just $45m for equity raised.

A few points:

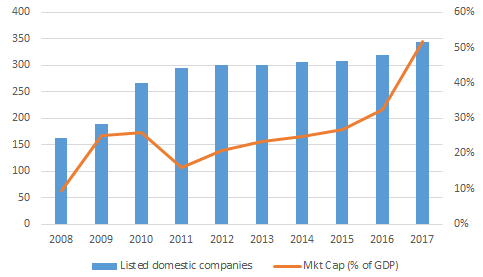

Source: World bank

Debt issuance is always much bigger than equity raising. That’s the way of the world. In Vietnam, the external debt stock in 2017 was $104bn, compared to GDP of $224bn. That doesn’t include internal debt. Market cap to GDP was 52%, which is close to just the external debt of Vietnam.

It doesn’t seem like all equity investments in public companies are being counted. The article says that only $45m has been raised in equity (I assume on the stock market in IPOs or secondary offerings), but we talked two days ago about $1.5bn in capital that Vingroup raised in 2019 so far. This vastly exceeds the amount that VinGroup raised in debt ($360m according to this article). Once you add in $1.5bn to $45m, it doesn’t seem so dire.

It also discounts private equity investment. Just looking at startups, they raised $246m through June and are expected to reach $800m, according to venture capitalists. And that doesn’t count equity investments in non-startups.

I think the point of the article is true: the stock market has not been performing up to expectations. We glanced on this a few days ago when we talked about correlations. The market (as evidenced by the VNM ETF) is up 7% (good), but not as much as the S&P (20%). That’s in the context of a booming Vietnamese economy that should be boosting earnings and therefore valuations.

Debt priced in USD is rising, and that’s not necessarily good. We have talked about this before, the mismatch between currencies with so many emerging market economies issuing debt in USD, but their revenues are mostly in local currencies. I used to cover Turkey, and Turkish companies would always issue USD-denominated debt because rates were so much lower (5% vs 18%+). But the currency would then depreciate, so in TRY-terms, the debt was much more expensive. And it happened all the time. You would think they would learn! Oh, and the currency usually depreciates when the economy is doing poorly, so it’s a double whammy.

Too much USD-dollar debt outside of the US can hamper Fed policy makers. Basically, if the Fed raises rates, then these companies may face a double threat of higher interest payments in an appreciating US currency. That would then hurt the economy, which, given globalization, will likely impact the US, forcing the Fed to lower rates. Or at least that is a path. The Fed probably won’t be raising rates any time soon, but they will at some point, and companies better be prepared for it.

September 11, 2019

Round up

There is a bunch of news about Vietnam, but nothing that is so big that it deserves a longer blog post. So today, I thought I would try to run through a few major stories:

Source: Khanh Day Nyugen (@ndkhans)

Vietnam Airlines can now fly to the US directly: This is long time coming, but Vietnam Airlines can now officially fly directly to North America. Cities included are: LA, San Fran, NYC, Seattle, Dallas, Vancouver, Montreal and Toronto. The big surprise on the list is Montreal. People with Vietnamese-origin made up just 1% of the city’s population and less than 50,000 total in the province in 2016, and the airport itself isn’t highly ranked in terms of traffic. I guess they just wanted to be comprehensive. I am more surprised by the cities left off: Chicago and Atlanta (huge hubs) and Houston (hub plus large ethnic ties).

Now, I doubt that Vietnam Airlines will start flying to all of these places. I assume it will start with LA and then expand if LA works. But it will be good to finally have a direct flight to/from the US.

Metro delayed, again: One step forward, one step back for transportation. You can now fly direct to LA, but you can’t ride a subway in HCMC until 2021. And they are talking about opening in the fourth quarter, which all but guarantees it won’t open until 2022. And the second line won’t be completed until 2024-2026 (so 2027). Traffic is a real problem. A metro is a real solution. Let’s do better people.

Vietnam will buy more US goods: This was another unsurprising announcement last week (in a Sept. 6 Financial Times story), and something I advised the government to do (see post on September 4, and, yes, I am sure that high level officials of the Vietnamese government read my blog). The Vietnamese government is worried by Trump’s rhetoric, and so it is trying to be as vocal as possible about how it doesn’t like the situation either. It will buy as many American goods as it possibly can, or die trying, goddammit! I expect this will do nothing to the trade balance, but it might help modulate Trump’s anger, which is arguably more important.

Swine flu claims almost 5 million pigs: I love pigs, and hypocritically, I also love pork. So it really kills me that 4.7 million pigs have been culled in Vietnam so far because of swine flu. They don’t get to live, and we don’t get to eat them! That’s almost a fifth of the country’s pigstock. It will probably get worse before its get better. When I had written about this before (July 11), 2.9m pigs had been culled. And there hasn’t been any progress on a vaccine, at least as far as I can tell. This might get worse unless the farmers and government get a handle on it.

Foreigners also causing traffic accidents: Foreigners are involved in 500 road accidents a year in Vietnam. Now that’s basically nothing compared to the number of total traffic deaths (around 23,000 in 2016, based on WHO data). But still, not a good luck for the foreigners. The video attached to the article is pretty funny. Lots of Western guys basically saying: I didn’t know the rules! Or the guy that rented me the motorbike should pay! Or lots of Vietnamese do it too, why am I singled out! I do think that educating the rental companies would be helpful. But ultimately, if you drive in a country, you gotta follow their rules.

September 10, 2019

VinGroup gets even bigger

News came out today that VinGroup received a $500m investment from GIC, the big Singapore sovereign fund. It is specifically in the VinCommerce subsidiary. This is the second big investment in VinGroup. Back in May 2018, it invested $853m in VinHomes prior to the IPO. In total, VinGroup has received $6.9bn through 15 transactions since 2013.

VinGroup is a beast with a market cap of $16.2bn (VND373tr), and VinCommerce is just a small portion of the business. VinCommerce is, as far as I understand it, the VinFast and VinFast+ stores plus some e-commerce. VinFast are supermarkets (121 in total), and VinFast+ has more than 1900+ convenience stores. Revenue at the division was VND19tr in 2018, a small portion of the VND122tr in total revenue for VinGroup. However, it is growing fast. Revenues in 1H were already VND14tr. One caveat is that is very difficult to know if the segment details in the financials/presentation, match revenues that GIC invested in. It could be that the subsidiary is more circumscribed that the full segment shows in the presentation.

These stores are losing money right now. According to the 1H2019 segment profit/loss, revenues for “retail services” were VND15tr resulting in a loss of VND2.2tr. Even adding back depreciation, the loss would still be almost VND2tr. In the presentation, consumer retail in the presentation had slightly lower revenue of VND14tr, and a gross profit of VND2.1tr. That’s a pretty low gross profit for a grocery business (even if it accounts for payroll), because other expenses like sales & marketing, overhead, etc, probably eat up the rest.

This is a big bet on VinGroup making grocery retail work. The revenue growth is there, in that they should really be able to get scale with all the stores they have now. And gross margin has improved drastically - gross profit was more in 1H2019 than it was in all of 2018. So the company is figuring it out.

Valuation? Based on VinGroup’s financials, it owned 64.3% of VinCommerce as of the end of 2Q. After this GIC investment, it still owns a majority stake. Let’s assume GIC got the best it could possibly get and VinGroup owns just 50.1% now. That means VinGroup sold around 14% of the sub for $500m, implying a total valuation of around $3.5bn, or about 20% of Vingroup. That equates to a P/S of 3.2x on a trailing basis. If the company just does what it did in 1H again in 2H, then P/S would be less than 3x. And it would be about 20x P/Gross profit.

Key points:

GIC is doubling down on VinGroup. It has a lot of other investment in Vietnam (back in October 2018 it was reported that GIC owns 5% of VietJet) as well.

A Korean company, SK Group, invested $1bn in Vingroup earlier this year. Part of this went into VinCommerce as well, so lots of foreign investors at looking at the sector and choosing VinGroup.

VinGroup’s strategy is to grow quickly through building, but also to acquire competitors. It bought Queenland Mart’s 8 supermarkets, and 87 convenience stores from Shop&Go in April. I couldn’t see acquisition costs, but

Market share is shifting away from traditional markets that should benefit all competitors. According to this article, 50-70% of essential food commodities come from traditional markets. And the traditional markets are not standing still - it looks like the government wants to support them. But I bet that a big portion of this consumption will move to more modern stores.

And because lots of companies agree with me, the retail market is extremely competitive, especially in the big cities. Circle K, 7 Eleven, Lotte Mart are all big foreign companies that are investing. And there are local competitors as well, including Co-op, which is as large as VinCommerce (in terms of supermarkets).

If we look at other very competitive markets, like the UK, competition really hurt grocery gross margin, because there was so much pricing pressure. Plus, stores need a certain level of sales in order to bear the costs of overhead, staff, and other non-variable costs. We could start to see this as the market matures.

It will be interesting to see if VinGroup can roll up stores quickly enough to forestall greater competition. They are getting the cash for it.

Ultimately, the investments in VinCommerce (based on my estimates, which could be off) seems really expensive. I did a quick scan of other grocery store chains, and most trade well below 1x sales. Even emerging market chains are trading below sales - MPPA, an Indonesia chain, trades at 0.1x, but even they don’t have the growth.

VinGroup itself is expensive. But it continues to attract a lot of money, and based on its filings, it would like to find 3 other big foreign investors.

Also, look for an IPO of VinCommerce. It is coming! Credit Suisse looks to be in the fast lane for this, based on the GIC investment.

September 9, 2019

Market correlations

So, I have been worried about my portfolio these days (which mostly consists of index funds), because of all the volatility around the trade war and Trumps tweets. Not to mention rising recession fears. But it turns out that the S&P 500 really hasn’t been that bad, down just 1.75% since its high, up 20% since the beginning of the year and still above where it has been for most of the year.

Surprisingly, the Vietnamese ETF, VNM, that I follow the closest (because it has the best data) has been a mess. It’s up 6.6% YTD, but down 8.5% from its high and below where it has been for most of the year.

If I was starting from first principles, I would have thought the reverse. While both performed not great in 2018 (the end of the year was a disaster), the S&P index is up 50% in the past 5 years while VNM fell 31%. Given a predilection to revert to the mean, you would think that VNM would do much better in 2019. And the story about Vietnam is just so strong: real GDP growth of almost 7%, main beneficiary of the US-China trade war, and an increasing political spotlight because of the US-N. Korea summit. Plus, no real inflation concerns, which can really hurt equity returns.

source: yahoo finance data, Vietecon.com

Well, I would have thought wrong. Still, I wanted to see how correlated the S&P500 and Vietnam’s stock market are. With the transmission mechanism being that Vietnam is a big trading partner with the US, gets lots of capital from the US, and, frankly, lots of stock markets internationally seem to be correlated. Based on data in this article, though, the S&P500 is not correlated well with an index of international equities when it is in a bull market, but is correlated when it is in a bear market (which is unfortunate for US investors that was diversification).

US & Vietnam stocks are loosely correlated: This data isn’t necessarily true for Vietnam. I ran a regression of changes in the S&P Index vs changes in VNM for the past 5 years. The adjusted-Rsquared is pretty low (0.3), but has a very low P-value, meaning that it is probably somewhat accurate. This equates to a the correlation found in times when the S&P is in a bull market. But it hasn’t been in a bull market over the past 5 years - both 2015 and 2018 were bad. So Vietnamese equities are somewhat different from international equities as a class.

But the markets do move in the same direction most of the time! I also did another test. I wanted to see if at least directionally the markets move together. When VNM is positive, is the S&P positive? Remember, over this period, VNM was down 31%, but the S&P was up 49%. So you wouldn’t think they would be moving together much. Well, you (and I) would again be wrong: They moved together 2/3rds of the time. I counted each time when both were up and when both were down.

That is strange. Not sure what that actually means, but it thought it was interesting. I wonder, if you just put a small bet on the S&P every day given what happened with the VNM, would you actually make money? It looks like it, or you would have over the past 5 years.

What I’m telling you is that if you use this proprietary data to make money, you owe me 2 and 20.

Not really. Good luck. It’s your grave.

September 6, 2019

Labour trends in Vietnam - urbanization

Continuing on from my post on August 2, I wanted to keep looking at the key insights from this ILO study of the labour force in Vietnam. Lots of interesting stuff here.

Source: World bank

One that piqued my interest was urbanization. On April 15, 2019, in the context of MMT, I talked a bit about urbanization, but I wanted to dive a little bit deeper now.

Where do we stand with urbanization in Vietnam?

In 2017, according to the World Bank, just 35%. So there is a lot of urbanization still to come.

In 1991, Vietnam was only 20% urbanized, and if we went back to 1960, it was just 15% urban.

Within ASEAN, Vietnam is similar to Laos and is only better than Cambodia. That seems strange to me. Vietnam is much richer than either one.

Malaysia is the most urban with 75% urbanization.

Looking ahead, urbanization is going to continue to be a major demographic change in the country.

The average annual growth of the urban labor force is 2.5% per year while the rural labour force rises just 0.4% per year.

Over the past few years, we have seen a significant decrease in the percentage of people working in agriculture. These are two sides of the same coin: there is urban migration to get away from agriculture jobs, but as farms consolidate (even at these nascent stages in Vietnam), that pushes urban migration.

At the same time as we are seeing all this urban migration, we are seeing more and more factories opening up, so manufacturing jobs. Again push and pull. More factories open up, means that more jobs pull people out of rural life. But also, factories come because they see that there are a lot of people.

One of the issues the report points out is that because most rural migrants are uneducated or under-educated, they face more difficulties finding a job.

In 2016, the unemployment rate of migrants was 9.3%; the unemployment rate among the youth migrants was up to 13.7%.

This probably overestimates the actual rate, because many of these migrants join the informal economy. But still, given that the unemployment rate was less than 2% at the end of 2017, there is a big discrepancy here.

This also means that these urban migrants are unlikely to push Vietnam to become a middle-income country. Education levels are low overall, but especially for the rural population. And that is going to take some time to fix.

Importantly, Vietnam, like China, has a residency system, so you can only get social services (including education) at your recorded residence. Updating your residence can be very expensive. In China, this effectively stops migrants from accessing services and moving up to the middle class. In Vietnam, they are making changes to at least the book itself (putting it online) in order to make it easier and more straightforward to update. There are still issues with accessing services, though, and this will likely cause problems for migrants’ ability to move up the economic ladder. Hopefully, with the system’s new database (expected in 2020), change will come faster.

September 5, 2019

Frogger in Vietnam

Source: Chris Slupski, @kslupski

I saw this article a few weeks ago, but wasn’t sure there was much to say about traffic in Vietnam. It’s bad! It’s crazy! Us Westerners have problems crossing the street.

The point is that even the Vietnamese authorities know that it’s crazy, and they are starting to take steps to address traffic issues. Maybe not by reducing it or getting people off the road, but to get them to drive a little bit safer. That includes drunk driving, which is really low-hanging fruit, but also speeding (a harder nut to crack) and “lane violations,” whatever that means.

Source: WHO

I wanted to see how bad driving is in Vietnam. Well, it turns out, pretty bad. I found some stats from the WHO that says that the situation is getting worse, at least from 2013 to 2016. In that latter year, 26 people for every 100,000 died from a road accident. Only Thailand is worse at almost 33 people, which was also up from 2013. In ASEAN, Singapore is the safest at 2.8 deaths, helped by very high car taxes, lots of cameras and a very punitive ticketing system.

I am someone who generally hates tickets, and I never believe I deserve them. So I can see why people in Singapore might complain about all of this. But to be frank, look at the results! They have one-tenth the number of road deaths than Vietnam and less than that for Thailand. The Philippines and Indonesia, while still much worse than Singapore at just over 12 deaths per 100,000 people in 2016, are still less than half of Vietnam.

Source: IHME, Global Burden of Disease

If we look at the cause of death, only Cambodia has a higher percentage of people that die from injuries. Their road deaths were “only” 17.8 people per 100,000 in 2016, so there are a lot of other injuries that kill people. Both Thailand and Vietnam are at 10% of all deaths caused by injuries. Southeast Asia as a whole is at 8%.

So, good for HCMC trying to deal with this. I wish they would do it by getting people off the road and only public transportation, but at least this is something.

September 4, 2019

Baby’s back! Plus trade data

I am finally back after a long time away. Hope you haven’t missed me too much, but I was busy doing…other things. Now I am back and will be posting regularly again.

The big thing that happened while I was away, at least in terms of economics, is that the trade war between the US and China has escalated, throwing markets (physical and stock) in disarray. That combined with weak manufacturing data in the UK, Malaysia, the US, Germany, among others, means that the sentiment is pretty negative worldwide. We are starting to see that with consumer sentiment in the US, where it has fallen to the lowest level since Trump took office. This is bad for Trump, and it is starting to show up in his polling. A majority of Americans disapprove of Trump’s handling of the economy. That’s new, and worrying for Trump. My view is that Trump’s overall approval ratings have held up only because of a strong economy. If the economy is bad or even if people just think it is, it is going to be hard for him to win reelection.

So what does this have to do with Vietnam. Well, just that the trade deficit is something that Trump talks about a lot, and Vietnam is now quite high up there, #6 in terms of balance of goods deficit. The charts below show the balance in goods for June 2019 and year-to-date as well as comparative figures for 2018. (The one on the left includes China, but then it is hard to see the rest, so the one on the left takes China out to see the rest). Vietnam has gotten much worse in absolute numbers rising from a deficit of $18bn to $25bn, although the ranking has remained the same.

If I were the Vietnamese seeing these figures, I would be pretty nervous. It is by far the most vulnerable of any of these countries - the EU can stand up for itself, and China too. Mexico is already negotiating, so that leaves Vietnam along with Malaysia and India as the ones that are under threat.

There is very little that Vietnam can do about this, especially because it continues to attract manufacturing and foreign direct investment. The most recent manufacturing PMI continues to be above 50 (an indication of expansion), albeit at a fairly low level. Unless it lets its currency rise (or forces it to), it seems unlikely to stop the trend.

But that’s fine! Just remember, these deficits have to be counterbalanced by capital & financials accounts. So the current account for the US is negative, but that means the capital and financial accounts have to be positive. It’s an equation that has to balance. So the deficit in the current account just means that the US is attracting money into its capital/financial accounts, lots of which is going into treasuries. But also into bonds and the stock market and businesses. Given that the US prints its own currency, it is very unlikely it will face a dangerous reversal in balances that could threaten the country.

Having said that, Trump really hates trade deficits, and the US has a big one with Vietnam. If I were going to advise the Vietnamese government, I would tell them to make as many declarations as possible about their desire to lower the deficit in the short term. And hope that Trump is too busy with China that he forgets about Vietnam. Then he loses in 2020.

The US Balance of Payments in goods in June 2019 compared to 2018.

The us balance of payments in june 2019 compared to june 2018

August 13, 2019

Real estate investments in Vietnam - the case of Keppel

Source: Vietecon.com, company data

This is actually from a few weeks ago, but Keppel, a Singaporean conglomerate, is making another big investment in Vietnam, purchasing a large (6.2 hectares or about 670,000 sqft). On it, they will build 2,400 premium apartments and about 160,000 of commercial space. This makes Keppel’s pipeline in Vietnam around 20,000 homes.

The article linked here actually has a fair amount of information on costs, so I thought it would be fun to try to NPV this investment. Of course, this entails a lot of assumptions, but let’s just assume that the figures are pretty much in the ball park.

First, we know the land cost (VND1.3tr) and the construction cost (VND6.1tr), as well as the apartment info and commercial space. Let’s assume that the sales price per sqft is around $230 (VND5.4m). That fits in with this article on pricing in HCMC.

These are supposed to be premium apartments, but let’s assume that the sizes are not too large at around 750 sqft on average, in order to keep the average price low at around $175,000 (VND4bn).

Then assume that the shops are sold (which is probably not the most realistic, but I didn’t want to model out a long-term rental, because…I’m lazy). I assume relatively small profit from the shops of VND189bn in total (or $8.2m).

coc = cost of capital. Source: Vietecon.com

Based on this, we get an NPV (at a cost of capital of 10%) for the project of VND643bn, or $28m and an IRR of 20%. (The full details are at the bottom of the post).

I would assume that this is fairly conservative, mainly given the size of the apartments are very low. If they were 1,000 sqft each, that would increase the NPV to more than $100m and IRR to 31%.

If separately, we lower the cost per sqft to $200 on average, the NPV actually turns negative (-$6m), but the IRR is still 13%.

If we combine both of those (lower cost per sqft but larger units), the NPV is above our base case at $62m and the IRR is 25%

We also assumed a cost of capital of 10%, which is quite high. I bet it is lower than this. If it is 1pp higher, NPV falls to $21m, but at 1pp lower, it increasesto $35m. Subtracting 2pp from the cost of capital gets us to $44m.

(See the table to the right for the sensitivity).

This is a pretty good deal for Keppel, as long as prices and demand hold up. The crackdown on corruption in Vietnam has made people nervous about selling land. That’s hurt supply as developers don’t have land to build on. After this deal Keppel has lots of land and a big pipeline of homes. Plus, they expect to start construction pretty soon (1Q2020) so they might be able to deliver why there is still limited inventory.

One more point, in our analysis, we assumed that Keppel doesn’t do any off-plan sales, meaning selling units and taking deposits well before units are delivered. If they can sell in advance and also pay their contractors on a delay, the cash returns just get better. That’s what all of the companies that I looked at in the Middle East did. It is a good way to juice returns on a smaller capital base.

all numbers in vndbn, unless otherwise noted. source: Vietecon.com

August 6, 2019

On Earth We’re Briefly Gorgeous by Ocean Vuong

Dear Readers: I forgot to tell you, I am taking some vacation over the next month (what it being August and all), and so I will be posting sporadically. Don’t worry, if something important comes up (remember, I don’t think anything is all that important in the great scheme of things), I will post something.

I just finished the book On Earth We’re Briefly Gorgeous by Ocean Vuong. This is one of the big books for the summer in the United States and the United Kingdom, although it’s not really a summer book. The reviews are very good. The Washington Post calls it “permanently stunning,” while NPR says it is “gorgeous all the way through,” and The Guardian says Vuong “mines his extraordinary family story with passion and beauty.”

The book is an epistolary novel in form – it is letter written to his illiterate mother. The form is only loosely used throughout the novel, but he does use the second person (you) to good effect. Also, it reads like memoir at points, probably because a part of it have been published as memoir (this part in the New Yorker).

The story is lyrical. It circles back on itself multiple times. It is also two parts smashed together. The first part is about his grandmother and mother, the second is about his first love with another boy named Trevor.

Interspersed are a few chapters that are basically prose poetry, or even just poetry, that alternate between varying subjects, including Tiger Woods and the opioid crisis in the US.

I found the first part almost too opaque, meaning that it was so difficult to follow what he was talking about that I put the book down and didn’t pick up for a week. The second part is more straightforward, even though there are those interspersed sections.

I don’t really like lyrical books. I like my poetry here, and my prose there. I guess I am just a plot person – I need plot to keep me interested. There is plot here, but that’s not why to read the novel.

In fact, I found the book a little bit annoying at times, because there were so many phrases that were just opaque and in some cases maybe too meangingful. So meaningful that they mean nothing. Like this:

It’s late in the season—which means the winter roses, in full bloom along the national bank, are suicide notes.

But then he writes something like this;

They say nothing lasts forever but they’re just scared it will last longer than they can love it.

Or this, which another reviewer point out:

The one good thing about national anthems is that we’re already on our feet, and therefore ready to run.

I really felt that the writing on the relationship between Trevor and the narrator was excellent. It showed a queer coming of age story that was so real, including very frank talk about sex between men. These scenes weren’t always beautiful (sex isn’t always), but it was entrancing.

I came away glad that I read the book and very much looking forward to reading more from Vuong. But I can’t say that the book itself was completely cohesive or really kept my attention at all times. That of course could be the fault of me, rather than Vuong.

In terms of Vietnam, Vuong, despite being born in Vietnam and speaking Vietnamese fluently, comes at the country as a tourist rather than a native. There is a scene with drag queens that come to help distract a family after the death of someone. That was fascinating, and something that I haven’t seen before and didn’t know about.

Overall, the book is worth reading, with some caveats that at times it is slow going and overly lyrical.

August 2, 2019

Emerging market flows

Yes, I am feeling much better. Thanks for asking (Editor: No one asked). Must be a summer cold or something. Still a little under the weather, but not too bad. (Editor: Yeah, no one really cares.)

Anyway, I promise to get back to the ILO report, because there is a lot in there. But right now, I wanted to talk about something that just came out in the news.

Emerging market flows fell a lot in July: $1.3 billion. Bond investments also fell by $100m. It was mostly China (negative $500m net inflows) and South Africa (negative $600m), but even Vietnam saw falls. In ASEAN, only Thailand saw inflows.

We actually haven’t seen an impact on the VNM ETF, which rose by a very small amount (+0.7%) from the end of June to today. That’s despite the depreciation of the VND.

Looking over the past few years, Vietnam has been doing quite good in the context of ASEAN. Net inflows since 2010 have been $4.35bn, compared to $8.3bn for Indonesia, $1.6bn for Malaysia and $11.7bn Thailand. On a per capita basis, Malaysia is doing just a bit better, $50 per person compared to Vietnam’s $46. Also, putting it like that, the investment seems pretty small!

But still, Vietnam had a great year last year (Indonesia, Malaysia and Thailand all had net equity outflows in 2018), and this year has been pretty good as well, despite July. Net equity inflows to China, meanwhile, are down almost 60% through June. That’s gotta hurt.

We have talked about this before: live by foreign capital, die by foreign capital. It can come and go quickly and capriciously. If you then have to invest a lot of hard currency to service this investment (say in energy, in inputs), a country could quickly come into problems with the currency, and then with defending the currency. It’s risky and limits maneuverability. That’s why I advocate at the least, heavy investment in renewables.

But good on Vietnam for taking advantage of the current trade war. Good luck not getting burned by the Trump administration going forward..

Source: IIF, Bloomberg

Source: iif, bloomberg

August 1, 2019

Sick day

Sorry, everyone, not feeling well today. Will catch up tomorrow.

Thanks!

July 31, 2019

Labour trends in Vietnam - aging

I am reading through a very interesting report on Vietnamese labor trends by the International Labor Organization. Full report here. It covers the period from 2012-2017 (although some of the data goes back more than that. A few things that seem to be key:

Source: world bank, vietecon.com calculations

The country had a demographic dividend (lots of young people) that is fading away as the population ages. We have talked about this before, but it bears repeating, especially as all these new foreign companies come to manufacture. It seems like the cut off age for these workers is something like 35, because it is just tough work. After that, they just don’t have the capacity to do it. Or not at the same level.

Right now (2018), the population is close to evenly split between above 35 (45%) and below (55%). This is expected to get worse over time. For example, people above 65 are 7.4% of the total population. This almost doubles to 14.7% by 2035, which is only 16 years away. The dependency ratio will increase to 50% by the same time, meaning that every 2 working age person needs to support an old or young person (with the increase mostly driven by old people).

What this means is that manufacturing really is only going to be a driver of growth for the next few years, before these people age out of it. Manufacturing will continue to be a big source of economic activity, but not of growth. And as the population ages and there are fewer workers, wages will likely rise. Conditions will also have to improve, in order to induce older people to work at the factories. But these new “costs” will very likely drive investors to put their factories in different countries.

The big drivers of job growth have been manufacturing and services. Eventually, growth will have to come from service jobs, which are less strenuous and allow people to work for longer.

Now, just to give a bit of support to these figures: I didn’t make up the figure for age 35 off the top of my head. This is something that is understood by both worker and employer. In fact, this story states it explicitly:

“It’s been like that for Xuyen for over 13 years. And soon, the factory is going to dismiss her because people over 30 are “not welcomed” there….Eighty percent of female workers over 35 in industrial facilities either quit or are forced to quit, according to the Ministry of Labor, Invalids and Social Affairs.”

Plus, there seems to be a view that two-thirds of the Vietnamese population is under the age of 35, but that’s not what the World Bank figures show - it is just 55% of the population (I double checked!).

More insights from the report tomorrow.

July 30, 2019

Goods trade surplus (this represents a deficit for the us), 2018. Source: US Census bureau by way of bloomberg

Trade and Beyond Meat

Just wanted to follow up on a few things:

First, US pressure on Vietnam is increasing, with the US Trade Representative, Robert Lighthizer, telling US lawmakers that “US businesses face a host of unfair trade barriers in Vietnam.” Through May the US had a trade deficit of more than $15bn with Vietnam. That’s a third of the total trade deficit with ASEAN. It’s the US’s sixth largest deficit in the world, similar to 2018 (see chart to the right). One of the problems, mentioned in the Politico story linked to above, is that the US has not been able to negotiate a trade deal with Vietnam, but Europe and the members of TPP have had trade deals implemented. That has allowed them to increase their exports to Vietnam, crowding out American goods. At the same time, more countries are moving production to Vietnam, mainly to export to the US, given the tariffs on Chinese goods and a few other products.

Second, just a quick update on Beyond Meat, which I wrote about on May 3, 2019 (scroll down to see that post).

The stock is way up since the IPO, almost 700%. That’s a great return. I should have bought some rather than pooh-poohing it. But I still think my analysis was correct.

The stock is way down: 17% from its high on July 26 and 12% today.

Results (announced yesterday) were good, and they have raised their guidance for revenue in 2019 to $240m, that’s way better than I had forecast and up $30m from new guidance in 1Q. They now look for adjusted EBITDA profit (which excludes a fair amount of stock expenses and some restructuring costs), compared to just break even. So it is very likely that they will get to profitability faster than I expected.

But the stock is down, because investors are selling stock. About 3.25m, compared to the initial IPO, where just 10m shares were sold. Of the new share sales, 250,000 are from the company directly. If it gets $200 per share, that would be $50m in additional cash for the company. I bet it will come in below that but still a good amount.

It already has $277m in cash, but spent about $33m in 1H2019. Since sales are increasing so quickly, we should expect working capital and capital expenses to be high, so the cash burn will likely continue for the next year or two at least.

One of the biggest cash expenses is Accounts Receivable, which grew to $34m at the end of 2Q2019. That’s a DSO of 76 days, up from 52 days at 2018 and 40 days at 2017. This means that it takes two and a half months for Beyond Meat to get paid for its sales. Tyson Food’s DSO is just 16.5 days.

This is partially offset by an improvement in Inventory Days, which were 93 days at the end of 2Q, compared to 157 days at 2018 but up from 85 from 2017. While the figure in 2Q is an improvement, it is still crazy high, especially for a perishable item. For comparison, Tyson Food has a DSO of 38 days, which still seems high but maybe it has something to do with the chickens being counted as inventory. That could be the issue with Beyond as well, they have to count the raw materials that stay at the factory longer.

So if DSOs and Inventory days fall, we should see some real improvement in the cash burn, and that seems like it will be pretty easy. That plus the cash balance they have now means that Beyond should be very well placed to grow, develop new products and get their name out there.

But I would still be wary about buying the stock, because it is super expensive. It is trading at 200x 2019 sales! SALES!!! ! That’s even with the updated revenue figure. This multiple falls pretty quickly, but unless they have a revenue CAGR of more than 60% through 2024 and/or have an operating margin of above 20%, I don’t see them trading below 50x P/E or 23x Price/Sales. That’s crazy high. Remember, this is a vegetable burger with implied sales of $1.5bn.

Right now the stock is in the dog house because of this extraordinary (in the sense of out of the ordinary) follow-on share sale so soon after the IPO. Once that is over, and if they beat estimates in 3Q, I bet we will see the stock start to perform well again.

Remember, I am not saying that the company is in trouble. The company is doing great, and the additional share sale is probably fairly smart. All’s I’m saying is that the stock is too expensive, and it is not worth getting ahead of the share sale.

July 29, 2019

Vietnam wins and loses some in the trade war, but mostly wins

Just wanted to put a few pieces together about the US-China trade war and US tariffs. On the positive side for Vietnam:

Apple is going to trial AirPod production in Vietnam, according to this story.

More mattresses in the US are coming from Vietnam. “Vietnam’s mattress imports are running at a current annualized rate of 1.3 million units, a level far below the 6.2 million unit rate peak achieved by China earlier this year, Raymond James noted.” Still, that seems pretty good to me.

Hasbro (a company I covered a really long time ago and the second largest toy company in the US/world) is moving manufacturing away from China to Vietnam and India. Still, there’s this: “Hasbro hopes to have only 50% of its products coming from China by the end of 2020.” So China is doing pretty well.

Here is an article that summarized the trends pretty well.

But some companies in Korea were too cute and tried to evade the trade war by sending production through Vietnam.

Turns out, the US Commerce department doesn’t buy that the steel is actually being manufactured in Vietnam, so it is slapping enormous tariffs on it. “The Commerce Department responded by slapping tariffs as high as 456.23 percent on those imports.”

Just a point here. So many companies have said that it would be impossible to shift supply chains or that it would take a long time. Remember when everyone said that Apple couldn’t move out of China. Well, it turns out that, sure, it can be hard to move production, but give it time, and things can be moved. It’s like the difference between fixed and variable costs. Over a certain time period, everything is variable! Over time, everything can be moved.

Also, some of this shifting supply chain is “a long time coming.” That’s because labor costs are rising in China, as are regulatory requirements around environmental issues. That’s on top of the uncertainty around trade.

The IMF just lowered world economic growth to 3.2% (from 3.3%), including China (-0.1pp) and ASEAN (-0.1pp), mostly because of weaker Chinese growth. It kept its forecast for real GDP growth at 6.5% for the next few years, but I wonder if China really starts to slow what that will mean for Vietnam. Right now the shifting trade looks good for Vietnam, but if China ever went through a recession, then Vietnam is going to do the same. As the cliche does not go, when China catches a cold, Vietnam sneezes.

July 26, 2019

South China Sea

This week I went to the Ninth Annual South China Sea Conference at CSIS. In the link, you can listen to all the panels, and you might even hear better than some of us did in the room! Surprisingly (or maybe not), this conference was just packed. There were very few empty seats in a room that probably sat more than 300 people. Many were professionals that work in the area, along with students and embassy folk. It was interesting to see.

A few takeaways from the first panel

From twitter @rdmartinson88

Indonesia: Probably won’t do much of anything, because Joko Widodo, the recently re-elected president, is really focused on domestic politics.

Philippines: Duterte has decided not to make a big deal about Chinese encroachment of Filipino waters, and so we have seen more and more Chinese fishing boats in them. The military is not happy about this, nor are the Filipino people, especially given fairly significant environment destruction by Chinese clam fishing. See this article about Chinese warships moving through Filipino waters without the government knowing.

Vietnam: Hanoi is pushing back against Chinese “survey” ships that are watching the Rosneft exploratory oil rig. It has continued operating despite the Chinese survey ship (see pics on right). The US is backing Vietnam in a way that it hasn’t before. Back in 2014, there was a similar dispute that resulted in first peaceful protests then violent protests in industrial zones against China. That hasn’t happened yet, and the government doesn’t really want it to.

China: According to the ex-Chinese Naval officers, China really just wants what the US has: freedom of navigation. It is not trying to militarize the South China Sea but every time that it is provoked by the US (he sited B-52 fly overs), it reacts by speeding up its deployment.

One thing that I found interesting was an answer to a question by Gregory Poling, who directs the Asia Maritime Transparency Initiative, which uses satellite imagery to show Chinese incursion in the South China Sea. He said that China controls the South China Sea more than it did 5 years ago, and that in 5 more years, unless someone does something, we just will have to all agree that it is theirs.

For Vietnam this has meant that oil & gas exploration has been limited by the Chinese activity. Vietnamese fishermen have also been harassed by the Chinese. This will likely get worse, unless Vietnam reaches some agreement with China (unlikely).

The second panel was about the history of the dispute. The best speaker was Bill Hayton, who was extremely clear and quite funny. He pointed out that a Chinese general recently said that “China had never invaded another country or taken land”. Of course, that seems to be countered by a number of times when China invaded islands or had border disputes. But in China’s eyes, all of these disputes were others encroaching on its sovereignty. It owned the land, so by definition it couldn’t be an invasion or seizure of land.

Hayton went through the history of China’s claims, and it sure seems like most of them are not serious/invented, mostly in 1948 (officially). Most of these claims won’t hold up in court (as we saw with the Philippines winning in the Permanent Court of Arbitration). Also, Taiwan has all of the records and could easily use them to discredit China’s claims. But that would result in repercussions against Taiwan, and it was unwilling to do that, unless there was support from the other claimants.

Stein Tonnesson had a slightly different timeline with a similar takeaway. Namely that China can’t really make a good case for most of these islands, but neither can anyone else. So they should just negotiate a solution with Vietnam taking some of the Spratleys, some of the Paracels, maybe Philippines and other players get different islands. China gets some too.

The ASEAN guy, who was a bit hard to follow, seemed the most optimistic about disputes with China. Maybe because he is Thai and has less of a dog in this fight.

Finally, Hayton made the point that these islands (in some cases, just features – not sure what that means, exactly), are small and meaningless. Who cares! Just divide them and move on! But I think the concerns the first panel had over fishing rights and oil & gas exploration means that these disputes are really not meaningless .

I do wonder why it matters so much for the US? It is a major seaway for a lot of trade, including to the US and Europe. Plus, it could be a spark that sets off conflict between China and its neighbors that could draw in the US.

July 25, 2019

Minh Phu - Buy Case

So today, I wanted to present a buy case for Minh Phu. There are a few reasons why I like the company:

Solid revenue growth: They seem very likely to get to at least exports of USD800m, which would boost sales by almost 9%. Guidance is for USD850m, but I am a bit worried about the second half, because the company is a bit behind what they did last year.

Long-term growth from Mitsui relationship: Overall, I think sales will benefit from the Mitsui relationship. Exports to Japan fell 6% last year and 17% through May of this year but has started to pick up (up 5% in June). The company did have a joint venture with Mitsui previously. In 2013, it invested in Minh Phu Hau Giang JSC (MPHG), a processing plant affiliated with Minh Phu.

New initiative could boost prices for Vietnamese shrimp: We talked about this two days ago, but the push towards inspections and sustainability may be able to push prices for Vietnamese. It will take a while, but in the long run could have a very big payoff. It helps that the company has $100m in additional powder from the Mitsui share sale. This is being invested in expanded farms, refrigeration in export markets and a breaded shrimp factory. All of which should help boost sales in the long term.

Shrimp consumption will continue to grow: One research report forecasts a 6.3% CAGR through 2024 for shrimp consumption. That’s seems fairly reasonable, given the push away from meat and towards more seafood in the West. I expect Vietnam will continue to be a big player in the market, and, especially if it can improve its reputation through these sustainability inspections, will be able to take share. MPC should also be able to take some share from smaller, less equipped exporters.

The change in ownership of MPHG boosts profits. MPC bought out Mitsui’s stake of 31% in MPHG which means that all earnings from the subsidiary will go to the parent now. Overall profits should improve by about VND50bn or 6% in 2019 and another VND50bn in 2020. This is based on 2018 minority interest of VND100bn. Let’s say that VND100bn represented the 31% ownership in MPHG, so that the subsidiary made around VND320bn. Based on this, the purchase of these shares was a good deal for MPC. It purchased the stake for VND872bn, or about 8.7x, in line with their 2018 P/E, so it wasn’t expensive. If revenue grows around 9% this year at the subsidiary, likely profits there will grow about 10%, so that the VND100bn is more like VND110bn. That makes the forward P/E just 8x, which is a good deal.

Valuation is very reasonable: We estimate the company is trading at a forward P/E of 7.6x. This would be 7.1x forward P/E if the company reaches guidance. Forward EV/EBITDA is 8.2x on our numbers. Those are extremely low, and much lower than any of the companies in the sector worldwide. We have 13 comps, with the cheapest one trading at 9.9x forward P/E. Clearwater and Huon Ag are a bit cheaper in terms of EV/EBITDA, but the rest are well above that, and the average is much higher.

Dividend helps provide floor: The company paid a dividend of VND5,000 per share in 2019 (off 2018 earnings. That is almost a 14% yield on today’s share price. They may not be able to keep this level, but even at half of that level, the yield would be good. The owners may be having cash flow issues of their own, which would like push them to keep making dividend payments at these levels. That helps other shareholders as well.

Upside from ETF: If MPC is added to the VNM ETF, there would be an underlying buyer at size (especially at the beginning), which should push the stock up.

Risks: I feel like the biggest risks are around revenues - prices for shrimp are falling, and MPC may not be able to offset that. Lower prices are likely to translate into lower margins as well, for a double hit. There is already the risk that MPC will not meet its guidance, which would likely hurt shares in the near term. But the longer term risk is that shrimp from Vietnam continues to be devalued in export markets. That’s why the sustainability initiatives are so important.

Target price: I don’t have a strong opinion on this. I would say if they were able to trade at 15x P/E, they would still be well below the average for comps, and it would be almost double from current levels, so I am setting my target is VND70,000 per share.

Continue to follow Vietecon.com to see how I do.

Source: company data, bloomberg, vietstock.com, vietecon.com calculations

July 24, 2019

Minh Phu

Source: company data

Yesterday, we talked a little about Minh Phu (MPC), one of the largest (if not largest) shrimp producers in Vietnam. They have about a 20% share, or did in 2018. It looks like it will be about the same this year or a bit more. That is despite a slightly worsening market for shrimp prices (and volumes). In the first half of 2019, prices fell again (2.4% yoy compared to 1H2018), although were up 2.3% versus 2H2018.

Revenues for the company have been all over the place, as you can see in the chart on the right. In fact, I am a bit worried that the figures for 2016 are incorrect, but they come straight from the horse’s mouth, as it were. What we can see is that generally revenues are trending up, but also more importantly, the gross profit is increasingly somewhat steadily.

Source: Company data, Vietecon.com calculations

That’s resulted in a much improved return on equity, which was negative in 2015 (the company had a net loss of VND19bn) to 22% in 2018. That’s a gigantic jump. At the same time, leverage is falling, as net debt fell from VND5.5tr to VND4.1tr in the same period.

As operations improve, the company has attractive interest from investors abroad. As I talked about yesterday, the company recently received a cash infusion from Mitsui, a large Japanese trading company. Minh Phu sold it 60m shares at a price of VND50,630 for a total of VND3.0 trillion, or $132m. That’s 30% of the company. The current market cap is VND7 trillion, or just over $300m. Unfortunately, this is still a fairly small cap stock, so many big investors can’t really invest in it. The reasoning is this: if you have $300m in assets to invest in Vietnam, you probably don’t want to put even one-twentieth of your fund in a stock that trades less than $500,000 a day. With 5% of your assets, you would need to buy $15m worth of stock, which would take more than 15 days to buy, and potentially more than that to sell, especially if things don’t work out and shares were falling.

However, MPC isn’t too far off from the lower end of market cap for stocks in the VNM ETF. A few stocks (NT2 VN, TCH VN) are just slightly bigger than MPC. The company could be a candidate for inclusions if the stock continues to rise.

Tomorrow I am going to look at valuation and what could drive the stock higher.

July 23, 2019

Shrimp from Vietnam

Photo by AM Fl @amfl

People in the West are having more and more concerns about where their food is coming from. This is especially true for seafood. Look at this list from EcoWatch, which is a list of all the seafood that I like to eat - the advice is to not! Then there is this article about shrimp from Consumer Reports (on EcoWatch’s website) - 60% of raw shrimp bought at US supermarkets tested positive for bacteria. Vietnam was on the list at 58% of the samples tainted, but even for Argentina and US wild caught shrimp, bacteria levels in samples were high (33% and 20%, respectively). Many samples also had antibiotic residue, which likely means that the shrimp were fed antibiotics, something that is not great for antibiotic resistance globally and should have stopped these from entering the US.

Seafood Watch by the Monterey Bay Aquarium is the main organization that makes recommendations in the US. In the UK, one organization is the Marine Conservation Society. I am sure other countries have the same thing. And they are sounding alarms about the source of most seafood.

Because of this background, I was happy to see this article about the Minh Phu Seafood company partnering with Seafood Watch to improve the sustainability of the Vietnamese shrimp business. The plan is to have self audits and independent audits in every province so that buyers can be assured that what they are buying is safe to eat. It will be interesting to see how they implement this.

The goal is to increase the sustainability and health of shrimp supplies in Vietnam. And of course to help exports, which are a big business. Shrimp exports are expected to exceed $4bn in 2019, up after a weak 2018 ($3.55bn, down 7.8% from 2017). See the chart on the left below with food exports from Vietnam.

Minh Phu actually bucked the overall trend, with the value of total exports up 8% in 2018, mostly due to volume (prices fell slightly). However, they did miss their guidance of $800m, but did $751m for the year. This equated to 21% market share, compared to 18% in 2017.

Year-to-date (through June), Minh Phu’s total export value was up just 1% ($286m), but signed contract value is for $425m, exactly half of their 2019 guidance of $850m. (See chart below on the right). The second half is always a bigger season. Again volumes are up more (3%) than value (1%), because of lower prices. This new initiative is clearly supposed to help the company’s and Vietnam’s competitive positioning, which should help volumes and potentially prices, if Vietnam can actually due sustainable aquaculture.