Final post on FRT (for the moment)

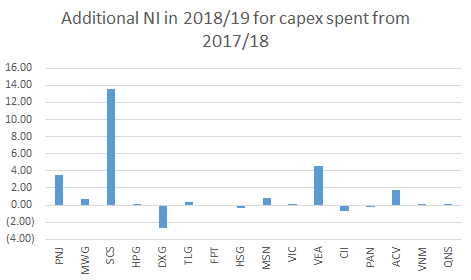

/There were a few more things about FRT that I wanted to look at today. First, a general comment: I believe that there is too much focus on income statements, especially with regard to consumer discretionary companies. Of course, revenues and margins are important, and we looked at them two days ago.

Source: Company data, chart by Vietecon.com

But the balance sheet is equally determinative of returns for shareholders. Remember the DuPont formula: net margin x return on assets x financial leverage = return on equity. And returns on equity are ultimately what (should) result in returns to shareholders.

FRT’s balance sheet is especially interesting, because it is similar in some ways to MWG (makes sense, both are consumer electronic companies), but the differences are illuminating.

Things that caught my attention:

Source: Company data, chart by Vietecon.com

DSOs: Days sales outstanding, which tells you how long it takes FRT to get paid for sales, is actually pretty long at 25 days. MWG was 6 days in 2019, and at the worst was 11.5 days (2017). I would think this is a cash business, so not sure why DSOs/receivables are so high.

Days inventory: This is how many days an item stays in the store, on average. This has been trending up, just as it has been at MWG, but it also isn’t as high as it is at MWG. As more stores open, it is likely that this will trend up, but the hope is that as the new stores reach maturity, it will fall again. Remember that inventory is ultimately cash in the form of products. If you can get a product in and sell it quickly, your returns are going to be much better.

Debt to equity: This is crazy high at almost 3x debt-to-equity. I thought MWG’s debt was bad, but it is nothing compared to FRT. While debt-to-equity has fallen, actual debt has increased - it’s just that equity has increased faster.

Return on equity: Remember that leverage matters a lot for returns on equity. And FRT is punching above its weight in RoE terms because of that high leverage. It was above 50% in 2016, and it only recently started to fall. In 2019 RoE was 17.5%, and because 1Q was weak, it fell to 14.5% for the TTM.

My biggest concern with this balance sheet is that it doesn’t provide much wiggle room for FRT. And right now, that’s needed. There is a potential very negative story to tell about FRT: Inventories are high, it takes a while for FRT to be paid by its customers, and to fund all of this, it has resorted to extreme levels of debt. But with COVID, margins are falling, and the ability to keep adding debt is harder.

But, I think that it is a bit too harsh. It looks like COVID will just be a small bump. And there is a real effort by the government to make sure that defaults are kept to a minimum by maintaining debt facilities and lowering interest rates, which should help FRT in the short term.

In the long term, D/E probably needs to fall, and that’s going to lower returns (all else being equal). So FRT really needs to focus on margins and inventory, to make that transition as light as possible.